‘I don’t have any other choice’ – refugee women’s journeys to Europe

We often think of irregular migrants to the EU as young, single men. But a third of those who cross the Mediterranean to seek asylum are women – these are their stories.

Refugees aiming to seek asylum in Europe frequently endure long, dangerous land and sea journeys.

The three main routes to Europe are across the eastern Mediterranean via Turkey to Greece, across the central Mediterranean via Libya to Italy, and across the western Mediterranean via Tunisia and Morocco to Spain. The central Mediterranean route is the most dangerous, but each of these journeys exposes migrants to extreme hardship.

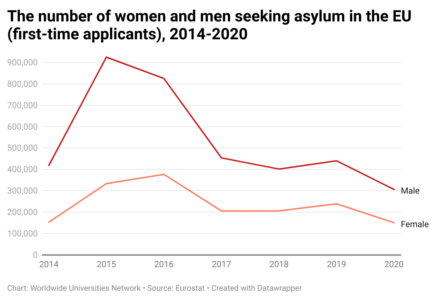

It is often assumed that young, single men are the main migrants travelling to Europe in this way, but a significant proportion of women are also making the journey. From 2014-2020, women accounted for 31% of first-time asylum seekers in the EU on average. In 2021, 30.4% of irregular migrant arrivals to the EU have been women and children.

This case study explores the experiences of Afghan, Eritrean and Syrian women as they travel to seek asylum in Europe. It compares experiences along the eastern Mediterranean route (used by Syrian and Afghan women) and the central Mediterranean route (used by Eritrean women). The 15 Eritrean women were interviewed in 2017, in reception facilities in Italy; the 13 Afghan and Syrian women were interviewed in 2019, in the communities where they lived in Turkey, and in reception facilities in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

‘The route seriously tortured us’

The women we interviewed had faced many risks on their journeys to Europe, crossing mountains, desert and sea to reach their destination. They travelled under the constant threat of being caught, detained and deported by police or border guards or being exploited and abused by kidnappers and the people they hired as smugglers. They endured hostile conditions in countries like Sudan, Libya and Turkey where some stayed before moving – or trying to move – onwards.

In Libya, on the central Mediterranean route, an industry of migrant kidnapping and exploitation has taken hold. Migrants there are systematically detained in appalling conditions and held to ransom. While they are being held against their will, they are often subjected to extreme violence, including torture and rape.

Migrant women are particularly vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence and exploitation – which was especially clear in the case of one Eritrean women, Abrehet, who was forced to marry and have children with the man who kidnapped her on her way from Sudan to Egypt.

In contrast, it was the violence of European border guards that shocked the Afghan and Syrian women we interviewed the most. As they attempted to reach Croatia on foot, through dangerous mountain passes and in freezing conditions, they were repelled by guards who beat them, confiscated their money, and destroyed their mobile phones.

‘The route seriously tortured us,’ Razan, a young Syrian mother in Bosnia and Herzegovina told us.

‘It’s not like it was for the others’

Many of the women we interviewed were travelling with small children, were pregnant, or had given birth at some point on their journey. Pregnancy and motherhood had a significant impact on their migration experience, by shaping their decisions about when to migrate, whether to take their children with them, and which countries to stay in or move onwards from.

Pregnancy and motherhood also affected the migration experience itself. On one hand, being pregnant increases the risks and difficulty of the route. On the other, women – especially if pregnant or travelling with young children – were sometimes spared some of the abuse and exploitation that their male counterparts suffered as the kidnappers and smugglers took mercy on them as mothers.

‘They beat me a few times, but because I had a child with me it’s not like it was for the others,’ said Abrehet, a young Eritrean mother interviewed in Italy.

‘I made my own decision’

Most of the women we interviewed showed significant resilience and perseverance. This was evident in their decisions to leave their countries of origin and then to travel onwards from countries that they did not consider to be safe places where they could build a future for themselves and their families. Many of the interviewees travelled independently for all or part of their journeys.

‘They didn’t want me to come this way;’ Eden, a young Eritrean woman told us when we interviewed her in Italy. ‘I made my own decision.’

However, it should be recognised that choice does not necessarily mean freedom. The women we interviewed had a very narrow range of options to choose from, all of which carried huge risks.

‘I really must take this risk. I don’t have any other choice.’

Bahar, a young Afghan woman interviewed in Turkey, explained that the UNHCR had recently offered her refugee resettlement in the United States. But the process would take four to five years and at the time, she was receiving threats from her violent ex-husband who had already attacked her family back in Afghanistan. Bahar was therefore making plans to travel irregularly to the EU because, although she would prefer to take the US option, she was fearful of what her ex-husband would do to her and her child if they stayed in Turkey. She knew her onwards journey to the EU could be fatal but, she told us, ‘I really must take this risk. I don’t have any other choice.’

The women we interviewed did not necessarily think of their decisions as real choices. Often, they were simply trying to find the least bad option available to them. In many cases, this was not necessarily the least risky option, but rather the one that offered them some measure of control over their own lives, and some hope for a better future.

‘We are tired here’

The Afghan and Syrian women we interviewed in 2019 were still en route and had not made it to the EU. They faced harsh border controls, violent pushbacks, and a lack of legal options to travel onwards.

Many of the women we interviewed had already been waiting several months, or even years, to continue their journeys, and were often living in very poor, precarious conditions. As one Afghan woman, a new mother, told us: ‘Whatever plans we had are destroyed, we just want to go somewhere to have a home. We are tired here.’

With the victory of the Taliban and the ongoing war in Tigray, the situations in Afghanistan, Eritrea and Ethiopia have significantly deteriorated in 2021, suggesting that more women will leave these countries in search of refuge and protection.

It can be expected that they will continue to seek protection in Europe, and will have to continue undertaking these long, hazardous and uncertain journeys due to the lack of options for travelling legally (for example, by air) to countries of asylum. Expanding legal pathways to allow women and their families to resettle in the EU from nearby countries should therefore be an urgent priority, so these dangerous journeys can be avoided.

This article is based on two research projects. The first, conducted in Italy at the European University Institute’s Global Governance Programme, was funded by a Rubicon grant of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). The second was the ‘Fluctuations in Migration Flows to Europe’ project commissioned by the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security.

Suggested further reading

Collyer, M. (2007). In-between places: Trans-Saharan transit migrants in Morocco and the fragmented journey to Europe. Antipode 39(4) 668-690.

Hagen-Zanker, J & Mallett, R. (2016). Journeys to Europe: The role of policy in migrant decision-making. Overseas Development Institute.

Kuschminder, K. (2020). Before disembarkation: Eritrean and Nigerian migrants’ journeys within Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Online First.

Kuschminder, K., Dubow T., Icduygu, A., Ustubici, A., Kiriscioglu, E., Engbersen, G. & Mitrovic, O. (2019). Decision making on the Balkan Route and the EU-Turkey Statement, The Hague: WODC.

The stories of women who migrated

'I never knew the journey was that risky' – women's experiences of corruption while migrating to Europe

Many irregular migrants to the European Union are driven out of their country of origin by corruption that makes daily life a struggle. But that corruption follows them en route in the form of bribery, violence and sextortion.

Read case study